Since the early 1960s and the civil rights movement, when urban concentrated poverty began to enter public consciousness, policymakers and neighborhood activists have pursued place-based anti-poverty work in distinct ways. Back then it proved difficult to address the multiplicity of issues that exist when so many people with low incomes all live in the same zip code. Today, it remains a difficult task—maybe even more so—given the disappearance of good manufacturing jobs, increased concentration of wealth, and political gridlock. Our country remains stubbornly segregated, and especially given how intertwined race and poverty are, it remains vitally important to focus on place.

Fortunately, we’ve had some new thinking on this front during the last eight years and I am guardedly optimistic that we are moving towards solutions.

Building on the work of social entrepreneur Geoffrey Canada, President Obama succeeded in funding the Promise Neighborhoods program centered on children in schools and, by extension, on their families. The initiative aims to improve educational and development outcomes for students living in urban and rural communities by providing cradle-to-career educational programs and family supports. Beyond the importance of the initiative itself is the fact that it opened the door to new approaches to fighting poverty. If a neighborhood revitalization initiative could be anchored in schools instead of the traditional focus on housing and community development, other hubs could serve the same purpose—including community health centers, or early childhood or mental health facilities, or a variety of family services locations.

This past year I visited four places to look at some of the cutting-edge work focused on poverty and place. The diversity of their theories of change is impressive, and all of them should be on our collective radar as we move into a new presidency.

Minneapolis, Northside Achievement Zone

I started in Minneapolis where I grew up. The city is perplexing. While it has a very low overall unemployment rate of 3.1 percent, the African-American poverty rate hovers over 44 percent and the African-American unemployment rate is about 14 percent (compared to 8.8 percent nationwide).

I visited the Northside Achievement Zone (NAZ), a Promise Neighborhood composed of a 13-by-18 block segment of North Minneapolis that is 84 percent African-American, with poverty above 50 percent, unemployment concomitantly high, and extensive violence.

NAZ was founded in 2011 with a mission to improve educational outcomes for children, including through parental involvement and a commitment to good housing, employment, and community safety. The heart of NAZ’s modus operandi is “connectors” and “navigators.” Connectors visit families in their homes and then connect them with the help they need. The connector brings the issue that a NAZ family is struggling with to a navigator who is a specialist in the relevant area—whether it’s related to education, parenting, child care, housing, or some other challenge.

NAZ works with partners of all kinds – including neighborhood-based organizations, businesses, education groups, and philanthropic organizations. In all, it has 43 ongoing partners and dozens more that it partners with when there is a specific need. It’s too early to draw any conclusions beyond the fact that NAZ’s work is promising, but if there is a second generation of Promise Neighborhoods—and I hope there is—we should keep an eye on NAZ and the work of connectors and navigators.

Chicago, Logan Square Neighborhood Association

The next stop for me was the Logan Square Neighborhood Association (LSNA) in Chicago, in business since 1962. Originally, the LSNA served mostly Polish Americans, but today it primarily serves Latino families. The LSNA engages its people in legislative advocacy and does a lot of community building as well. Its long list of activities includes: affordable housing and foreclosure prevention, education programs for children and adults, investing in green development, and addressing immigration issues, among others. There is no one place to find money for all of that work, so the LSNA stitches together its budget from dozens of sources—government at all levels, philanthropic, corporate, and individual.

I visited LSNA because of its parent mentor program, which operates in nine local public schools and directly impacts more than 3,800 students. LSNA recruits parents (usually immigrants) of children in kindergarten to come to school as semi-volunteers—they receive a small stipend at the end of each semester. The parents are nurtured into mentor roles, including by obtaining a GED. Finally, they graduate to employment—at LSNA, the school where they volunteered, or elsewhere—or they further their education. The women involved in the program successfully lobbied the state legislature for an appropriation. That’s good stuff. Put it on the agenda for national attention.

Los Angeles, Youth Policy Institute

The third stop was the Youth Policy Institute (YPI) in Los Angeles. This one is special for me because its CEO, Dixon Slingerland, worked for Robert Kennedy’s dear friend (and mine), David Hackett. Among other things, Hackett founded YPI and helped establish what we now know as AmeriCorps Vista. When he retired in 1996, Hackett passed the mantle to Slingerland. He died about 5 years ago, and I know he would be very proud of the work YPI is doing today.

You have to catch your breath at the size of what Slingerland and his colleagues have built. YPI’s budget has grown to $57 million. It has 1,600 staff serving more than 100,000 youth and adults at 125 program sites. YPI is the lead agency for a Promise Neighborhood, a Byrne Criminal Justice grantee (to reduce neighborhood crime and increase safety), and a lead partner for a Promise Zone. It operates five schools of its own and partners with 90 more, 83 public computer centers, and runs afterschool programs at 78 schools.

YPI is an example of what the nonprofit sector can do by marshaling public and private funding to help children and families at scale. I visited two of YPI’s non-school sites and talked to many staff members and even more consumers of the products. They serve children ranging from early Head Start, to older students in after school and gang prevention programs. They also offer teen pregnancy prevention, job readiness, and job placement services. YPI works with families on parenting skills, financial planning, and computer literacy. They help day laborers and teach community agriculture. Nonetheless, Dixon is very clear that for all the help YPI extends to individual children, youth, and families, the strategic point is to change things on a large scale as well. I think the lesson here is that YPI and similar organizations must have public and private investment for what they do, and that their ultimate goal is to move the needle on poverty.

New Haven, MOMS Partnership

Finally, I visited New Haven and the New Haven Mental Health Outreach for Mothers (MOMS) Partnership, an innovative collaboration of city agencies and institutions that was spearheaded by Megan Smith, a faculty member of the Yale School of Medicine. This is a relatively young endeavor but it has already received national attention and funding from the university, foundations, the state of Connecticut, and the federal government.

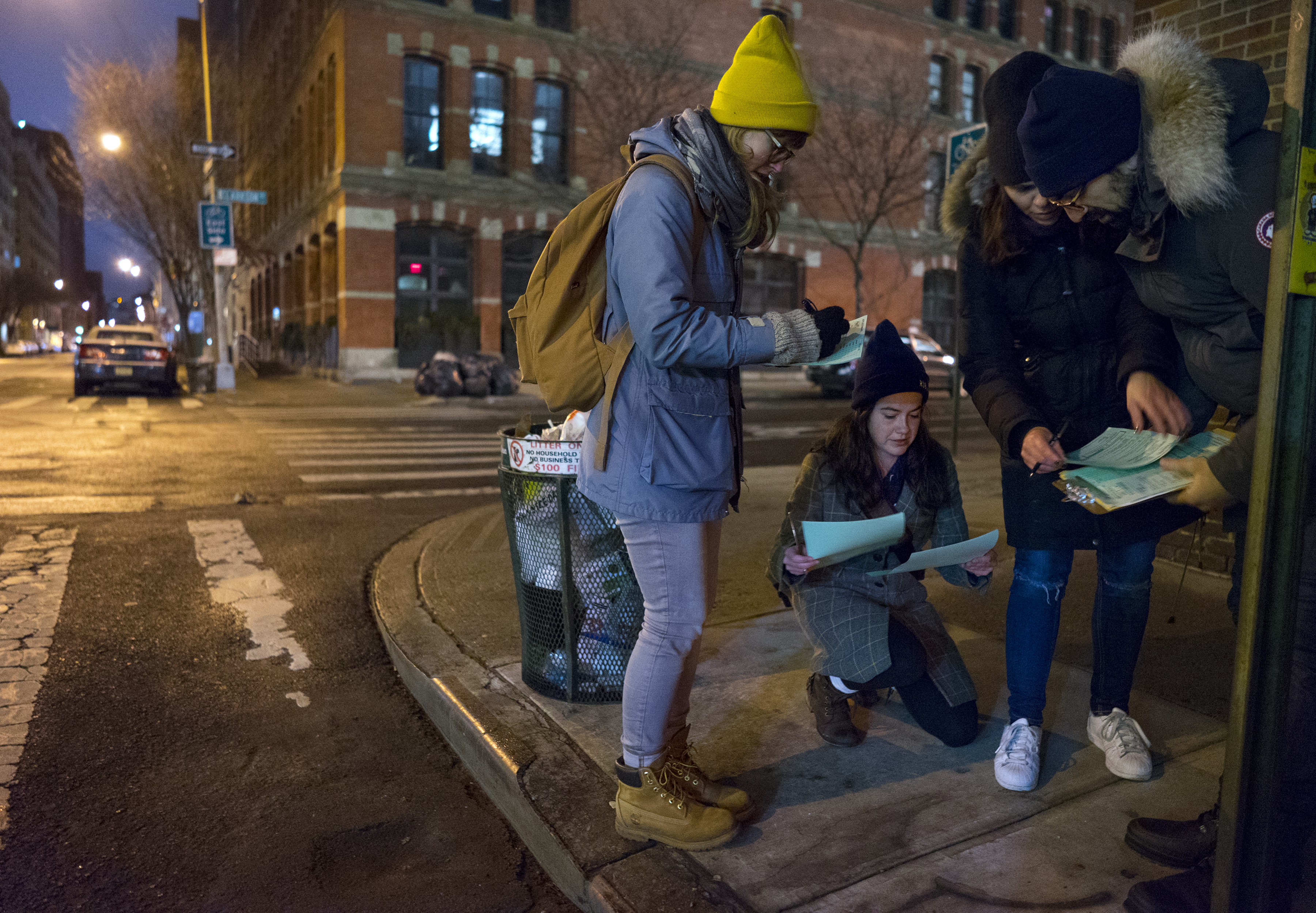

The exciting thing about the MOMS Partnership is its focus on mental health. The entry point to get women involved is by addressing the extra stress that comes with living in poverty and near poverty. With decentralized locations in the community, Smith’s staff—who are themselves mostly residents in low-income neighborhoods—do outreach to their neighbors and offer an 8-week stress management course to address chronic and toxic stress. Participants also have the opportunity to take skill-building and job readiness classes. The MOMS Partnership is currently branching out, and is especially expanding its effort to help participants find employment or job training.

These four diverse initiatives are representative of innovation that is occurring throughout the country. Attacking the many issues that confront people who live in low-income neighborhoods is a longtime challenge. It is vital that we support these and other efforts so we achieve a scale large enough to make a measureable difference in the fight against poverty in America.