Earlier this week, Speaker Paul Ryan and Senator Ron Johnson, both of Wisconsin, penned an op-ed stating—once again—their belief that charity and individual responsibility are the key to fighting poverty.

“This is how you fight poverty: person to person,” they write.

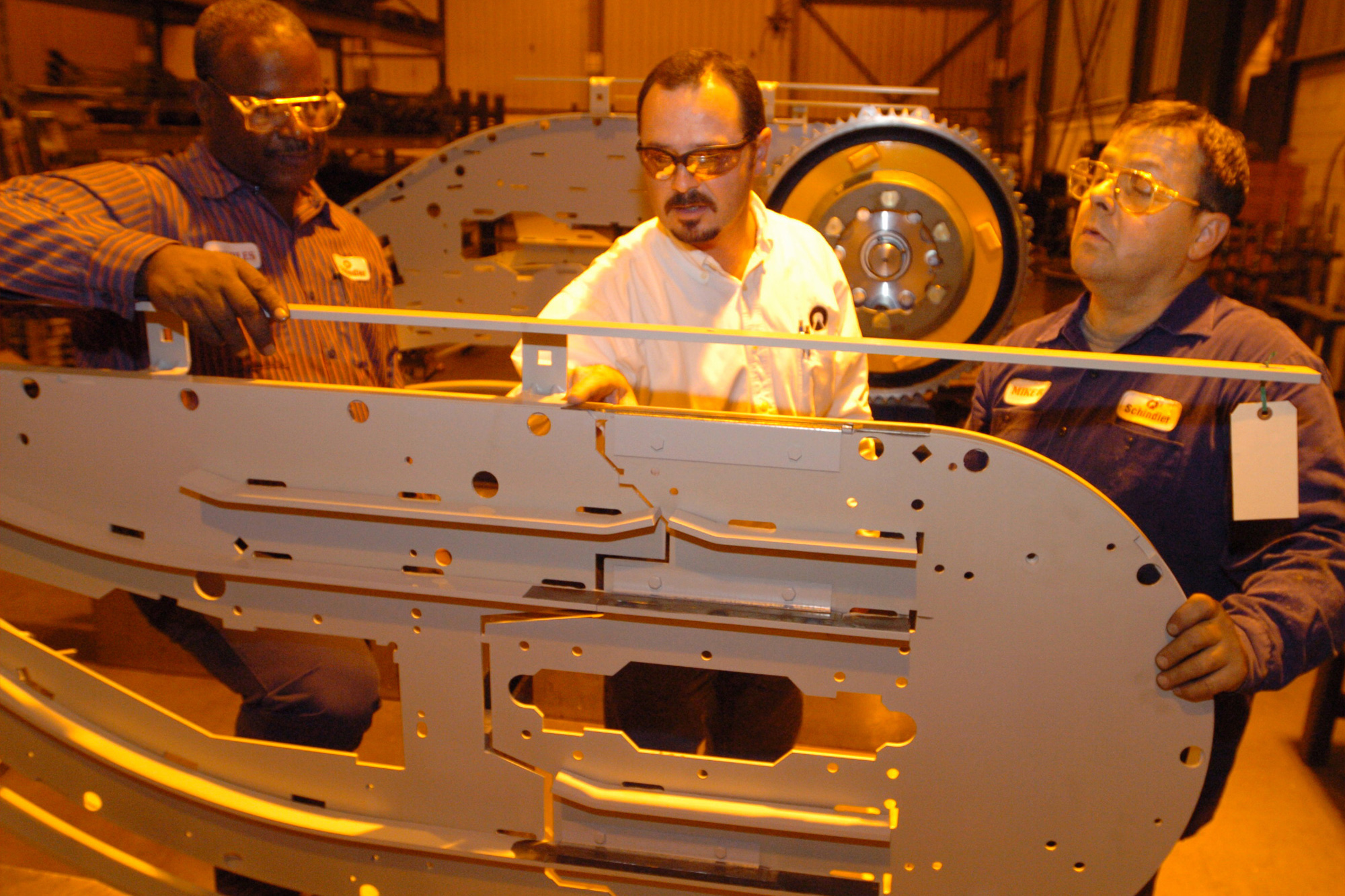

To illustrate their point, they tell the story of The Joseph Project, a job assistance program run by the Greater Praise Church of God in Christ in Milwaukee. Ryan and Johnson praise The Joseph Project for providing vans that drive Milwaukeeans to Sheboygan County, where they can earn $15 an hour working a factory job. In Milwaukee, by contrast, these workers would likely earn just $8 or $9 an hour. The drive is an hour commute each way, but Ryan and Johnson assert: “That van represents the difference between poverty and opportunity.”

Get TalkPoverty In Your Inbox

While it’s important that The Joseph Project is assisting these folks, it’s disingenuous for the Speaker and the Senator to lift up this kind of program as the key to fighting poverty—and even a justification for overhauling our safety net.

The reality is that supporting an adequate minimum wage could also be the difference between poverty and opportunity for these workers. By supporting a minimum wage raise, Ryan could help put an end to poverty wages and save those same workers the two hours they spend each day riding in that van—giving them back some of the family time that Ryan cherishes so much in his own life.

To help the Speaker understand why his take on fighting poverty is so flawed, I suggest he return to the source he often cites as inspiration for his anti-poverty proposals: Catholicism.

In Sunday school classrooms across the country, young Catholics are taught the simplest versions of the Catholic Church’s complicated theology: God’s love is represented by loving parents, Bible stories are boiled down to picture books, and stewardship of creation is taught by tending to one’s own little plant. And one Sunday school classic, “The Two Feet of Love in Action,” makes it clear that larger systemic solutions are integral to fighting poverty.

“There are two different, but complimentary, ways we can walk the path of love,” the United States Conference of Catholic Bishops explains. “We call these ‘The Two Feet of Love in Action.’” One foot is charity: direct service to help meet the immediate needs of individuals. The other foot is social justice: structural change to end the root causes of poverty.

The van is charity; the minimum wage hike is social justice.

Like Ryan, the Catholic Church values charity and applauds the commitment of faith communities like Greater Praise Church that provide direct assistance when people are in need. But, with its commitment to social justice as well, the Church might have some questions about why Ryan is trying to step with just one foot to end poverty. The bishops might even ask why the Speaker hasn’t joined a living wage campaign—one of the examples of social justice on their Two Feet flier.

It serves Ryan’s politics (and budgets) to let charity and other local efforts subsume broader anti-poverty initiatives, to diminish the work of the federal government in curbing poverty, and to pretend we can make meaningful change without making systemic change. But when people who are struggling turn to WIC, the EITC, or SNAP, that’s not dependence—it’s interdependence.

Giving from those who have more to those who have less on a person to person basis is charity, and it’s good. Giving from those who have more to those who have less on a systemic level—making changes to ensure our tax code is fair, passing laws to increase the minimum wage, and ensuring our anti-poverty programs are more robust, not less—is justice, and it’s necessary.

We need charity and social justice to end poverty. Any Sunday school student could teach Speaker Ryan that.