The government wants to make it much harder for workers to hold employers accountable for wage theft, hours violations, and unionbusting by complicating the answer to a simple question: Who do you work for?

Historically, if two entities oversee aspects of someone’s work experience — such as wages, hours, and policies — either separately or together, they could be considered “joint employers,” which means they are both liable for labor violations. While this standard isn’t used very often, it can be a powerful tool for holding large corporations accountable.

Think contractors who work alongside direct employees, doing the same work at a site where the parent company controls hours and policies, the staffing company handles payroll and employee screening, and both have hiring and firing rights. If workers filed a complaint, a judge might determine that the worksite and staffing company are joint employers, depending on the specific facts of the case.

Now, after a failed attempt at narrowing the definition of a joint employer in Congress in 2017, the Trump administration is turning to the regulatory process to make it harder for workers to file claims that rely on this standard.

When Congress passed the Fair Labor Standards Act in 1937, it explicitly acknowledged that some workers, in disputes over wages, hours, and child labor practices, might be in a joint employer position. The question has been a subject of back and forth litigation and rulemaking because of the high stakes. The landmark Browning-Ferris case in 2015, which briefly established more protections for people making joint employer claims, allowed workers to leverage bigger wins and push for a larger culture of change. (Currently, a combination of litigation and rulemaking have the ruling’s status in flux.)

Get Talk Poverty In Your Inbox

The Department of Labor recently announced a proposed rule to narrow the standards of who counts as a “joint employer” under the FLSA. It is extremely restrictive, requiring companies to meet a highly specific four-point test and disallowing consideration of other factors. For example, if a contract includes hiring and firing rights for the parent company but they aren’t exercised, the court couldn’t consider that, and the parties would fail the joint employer test; the parent company would not be liable for damages.

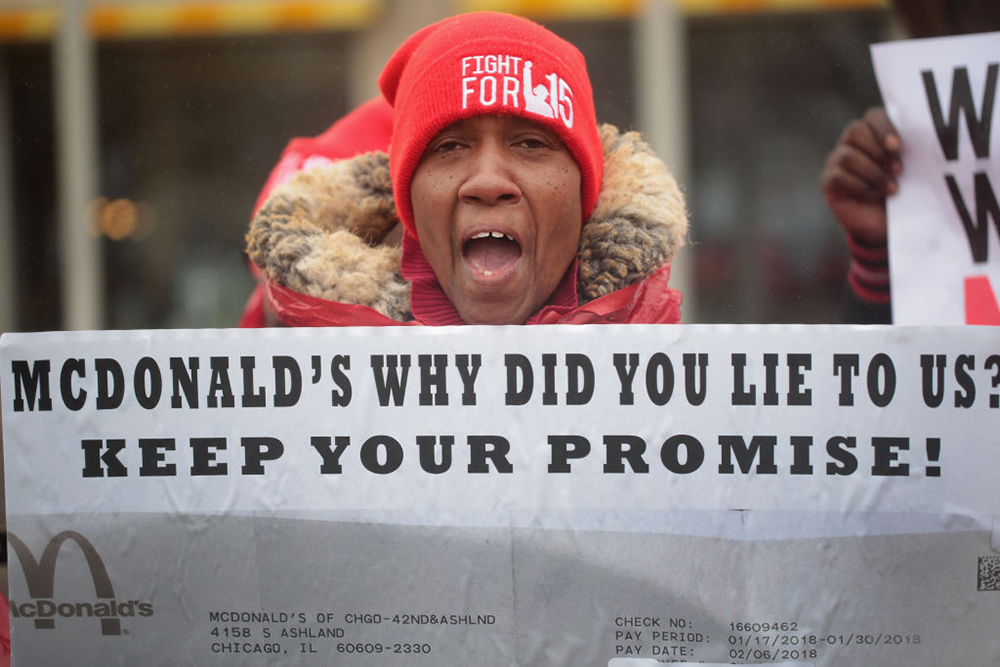

Much news coverage on the administration’s attempt has focused on what it means for fast food workers, who often work in franchises with a parent company and local owner. But the implications are even bigger, affecting millions of workers across the economy in the garment, agricultural, construction, hospitality, and building services industries, among others. It’s an especially important distinction for people caught in the dramatic increase in “contingent labor” in recent years.

It also affects third-party logistics (3PL) employees who handle outsourced elements of the supply chain such as packaging, delivery, warehouse maintenance, and more. Think forklift operators at factory warehouses and delivery drivers. 3PL is one of the biggest areas of growth, according to Tia Koonse, Legal and Policy Research Manager at the UCLA Labor Center. 86 percent of Fortune 500 companies are using third-party logistics agencies, outsourcing labor along with liabilities to increase profits. Nearly half of Google’s workforce, for example, is not directly employed by Google.

“I think that this [proposed rule] is aimed at workers who have spoken up, and the workers are not going to back down,” commented Jonnee Bentley, associate general counsel at SEIU. Fight for $15 worker-organizers have achieved significant victories across the U.S. in recent years; for example, there was a 2014 NLRB ruling in favor of McDonald’s workers who complained about retaliation for labor organizing.

As part of its proposed rule, the Department of Labor provided a handy breakdown of hypothetical examples for people wondering how different scenarios might be interpreted under the new rule, which reads more like a how-to on avoiding a joint employer determination. It’s also heavily stacked with examples from fast food franchises, although according to Catherine K. Ruckelshaus, general counsel at the National Employment Law Project, franchises haven’t been involved in joint employer disputes under the FLSA.

Curiously, though the rule touts cost savings for business, the only costs calculated in the current draft available for comment are $420 million in expenses associated with implementation. Under the Obama administration, franchise growth consistently outperformed the private sector, suggesting that increasing joint employer protections did not harm business growth.

– Jonnee Bentley

Undermining the way employers and courts interpret the FLSA isn’t the only way the Trump administration is using the rulemaking process to make it harder to bring joint employer claims. Last year, the NLRB announced a proposed rule, not yet finalized, to redefine the interpretation of the joint employer standard in the National Labor Relations Act, the legislation that surrounds worker organizing and labor disputes: If workers want to start a union, complain about unionbusting activity, or get support with the fight for a fair contract, they need the NLRB.

The NLRB wants to shift the joint employer definition to one that requires direct and immediate control of working conditions, moving away from broader Obama-era guidance that also accounted for “indirect control,” such as exerting guidance over business practices or providing software used to run a business.

The change would be good news for companies such as McDonald’s, as it would make it more likely that the corporation would not be considered a joint employer of franchise employees for the purpose of trying to unionize, and would have no obligation to come to the table to bargain. The franchise operator, meanwhile, would have limited options for meeting worker demands, because of price setting and other dictates set by the corporation. It should be noted that even in a case where franchise employees did manage to prove joint employer status and win a union contract, it wouldn’t automatically apply to other franchises — but the win could help workers organizing at other locations.

That these two proposals are similar is not a coincidence, Bentley said. “They’re trying to make it easier for big corporations to avoid liability by using contractors or franchisers.” The Obama-era guidance has enabled workers to hold franchises accountable for violations in the past.

“It’s part of the systematic dismantling of gains made in the previous administration,” said Koonse. “I feel the [Department of Labor] rule does not hold joint employers accountable in the way Congress intended,” she added, noting that the definition as proposed is so narrow that it may not withstand legal scrutiny.

The push through multiple venues to make it harder for workers to hold joint employers accountable is part of a larger pattern of attacks on labor rights, such as undermining overtime rules, cutting numbers of OSHA inspectors, and cutting billions of dollars in funding from the Black Lung Disability Trust, which supports coal miners living with black lung disease. One of Trump’s earliest cabinet appointments was to name fast-food giant Andrew Puzder secretary of labor — Puzder ended up withdrawing after outcry, but the initial nomination signaled a much more business-friendly approach to worker rights and protections. Working to unwind rulemaking from prior administrations and develop more restrictive interpretations of the law fulfills the president’s deregulation mandate, at a high cost to workers.