When Benny Lacayo was released from prison after two and a half years, he had a rough time transitioning. “To try to reconnect, and gain that humanity back, that’s very hard,” he reflected. Reentry was an emotionally overwhelming experience, and the myriad requirements of his parole — and lack of support from the state — made his transition more difficult. Probation and parole typically restrict where someone can live and work, who they can socialize with, where they can travel, and more. People must also regularly report to a supervising officer. “[Probation or parole officers] are trained to help in a certain way, and the way they’re trained doesn’t help,” he says. “[It can] cause more problems and conflict and cause you not to seek help.”

Lacayo is one of the 4.5 million people on probation or parole on any given day in the U.S., almost twice as many people as are currently incarcerated. Community supervision is often thought of as a positive alternative to incarceration. But for many, the strict requirements and intense surveillance turn it into “a secondary form of incarceration,” says Amy Sings in the Timber, an attorney and executive director of the Montana Innocence Project. The consequences for not adhering to the conditions of parole are harsh: A quarter of state prison admissions nationwide are a result of technical violations such as failing a drug test or missing a meeting with a probation or parole officer. “In many instances, in our client populations, there are survival tactics that are criminalized,” reflects Sings in the Timber.

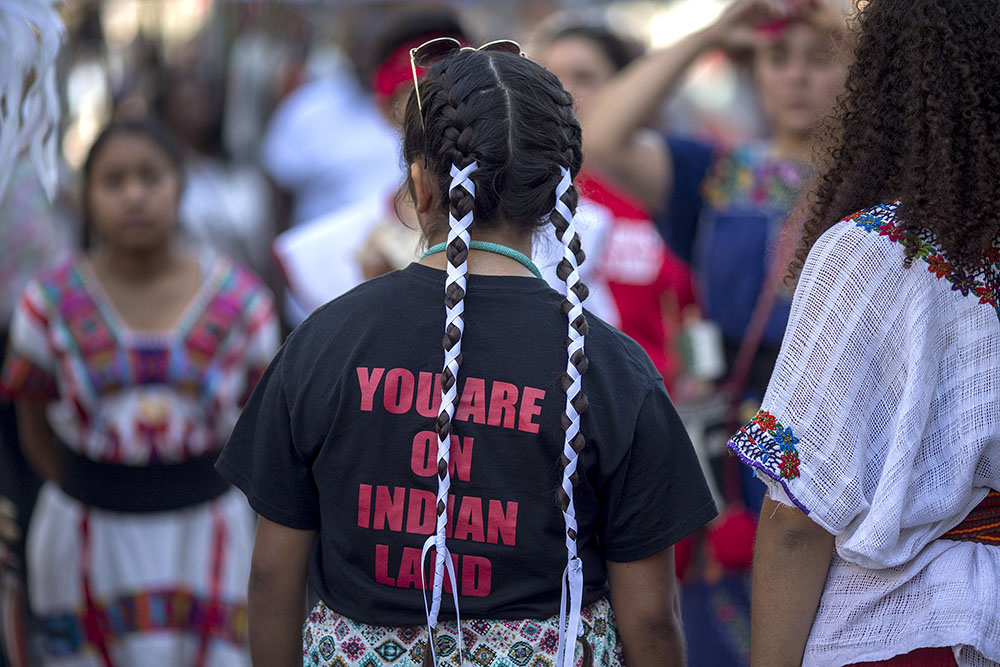

The issue is acute in rural states such as Montana, and disproportionately impacts tribal communities. Native Americans account for 6.5 percent of Montana’s population, but represent 20 percent of the population in men’s prisons and 34 percent of the population in women’s prisons. An ACLU report found that between 2010 and 2017, 81 percent of Native Americans in Montana who were reincarcerated while on probation were charged with a technical violation, not a new crime.

Technical violations send people back to prison because of a lack of support

Complying with requirements of probation or parole can be a high-stakes experience and the system is not set up to help people navigate the complicated network of needs post-release. The threat of punishment makes some fearful to reach out for help, said Lacayo, who is now a community organizer. “[Probation or parole officers] could easily make your life even harder, so it’s very hard to say how you feel,” Lacayo reflected.

There are also a number of practical barriers.

Many conditions of probation or parole require transportation, and in Montana, people may have to drive over an hour on rural highways to reach the nearest probation and parole office. “To be able to even access your supervisor can be impossible in some instances,” says Sings in the Timber. These long trips are frequent, especially since the Montana Department of Corrections does not accept most urinalysis and drug testing, evaluations, or treatment programs that take place on reservations. Some tribes, like the Fort Peck Reservation in eastern Montana, have a memorandum of understanding with the state that allows tribal members to utilize the tribe’s probation and parole resources to fulfil state requirements. However, this is not a state-wide standard.

Housing is another common requirement of probation and parole, and Montana has 23 housing-related collateral consequence laws that restrict or ban certain forms of housing for formerly incarcerated people with certain convictions. Even pre-release centers — transitional facilities where formerly incarcerated people live under supervision — can be challenging to access, though they are meant to be a stepping stone to independent housing. All pre-release centers in Montana are in urban areas; none are located on reservations. Lacayo also notes that they are not always designed to be a supportive transitional environment. “When I got to pre-release, one of the directors said ‘Just so you know, I’m not here to be your friend,’” he says. “They have absolute power over you. That’s a very scary thought.” At the time Lacayo lived there, it cost $14 per day. Montanans earn between just 16 cents and $1.25 per hour for employment while incarcerated.

Montana also has 189 employment-related collateral consequences, including bans on many jobs that require occupational licensing, such as commercial truck driving and selling real estate. (One in four jobs in America requires such licensing.) Some of these consequences are mandatory and lifelong, while others are at the discretion of the employer and time limited. Reservations have a separate set of laws, with their own restrictions. Some, including the Fort Peck Reservation, ban anyone with a felony from working for the tribal government, which is often the largest employer in the area. It can be a confusing system to navigate. “The number of employment opportunities are far and few between,” says Sings in the Timber.

Reentry is also expensive. Costs associated with probation and parole — such as mandatory drug tests, restitution, or GPS monitoring — can quickly add up. Compliance Monitoring Services, one of the companies Montana courts use for surveillance, charges up to $360 per month for GPS bracelets, plus a $50 installation fee. If someone can’t afford rent or other fees of probation and parole, the Department of Corrections can garnish their wages, tax refunds, or a tribal member’s per capita payment.

Reentry supports reduce technical violations and recidivism

Social support can be particularly hard to come by as a formerly incarcerated person. A common condition of probation or parole is that you are not allowed to associate with other formerly incarcerated people — especially challenging in small communities or if family members are formerly incarcerated.

Returning to a reservation presents a separate set of barriers. As sovereign nations, reservations do not fall under the jurisdiction of the state. This means that people on probation or parole cannot legally return to their home reservations without extradition waivers, which allowing the state to extradite someone from tribal jurisdiction if a violation occurs. Not all reservations have extradition waiver agreements, however. The Fort Peck Reservation in eastern Montana does, while the Crow Reservation in central Montana does not. Without an extradition waiver, people cannot live on a reservation until they have completed their probation or parole, which may be years.

“It’s almost impossible for [people on probation or parole] without their support system,” reflected Fort Peck Chief Judge Stacie Four Star. “But we see that a lot.” Four Star is pushing for standard memorandums of understanding and extradition agreements statewide, but these ideas have gained little traction.

Recent policy efforts to increase support for formerly incarcerated Native Americans have been unsuccessful. Two bills were introduced in 2019, which would have created a grant program for culturally-based reentry programs and revised an existing reentry housing grant program to require that a certain percentage of funding was allocated to programs serving Native Americans. Neither bill passed. There has been more success with tribal-led programs. The Confederated Salish and Kootenai Tribes Holistic Defender Program, for example, assists clients to find employment, housing, healthcare, obtain a drivers license, and connects people with mentors, such as tribal elders, to provide cultural support.

The pandemic has expedited the need for improved reentry support. In spring 2020, Indigenous and Latinx activists in Montana, including Lacayo, organized a campaign called Let Them Come Home to advocate for an end to arrests for technical violations, temporarily waive probation and parole requirements, and reduce the number of people in Montana jails and prisons. Despite their efforts, Montana actually released fewer people from prison in 2020 than they did in 2019.

Without meaningful reentry support, technical violations will likely continue and people will continue to be re-incarcerated. “How can you jump through all these hoops and follow the rules if you don’t know where your next meal is coming from or where you can sleep safely?” reflected Sings in the Timber. “We need to take a look at technical violations not as someone willfully doing wrong, but as a strong sign that there is support that is needed.”